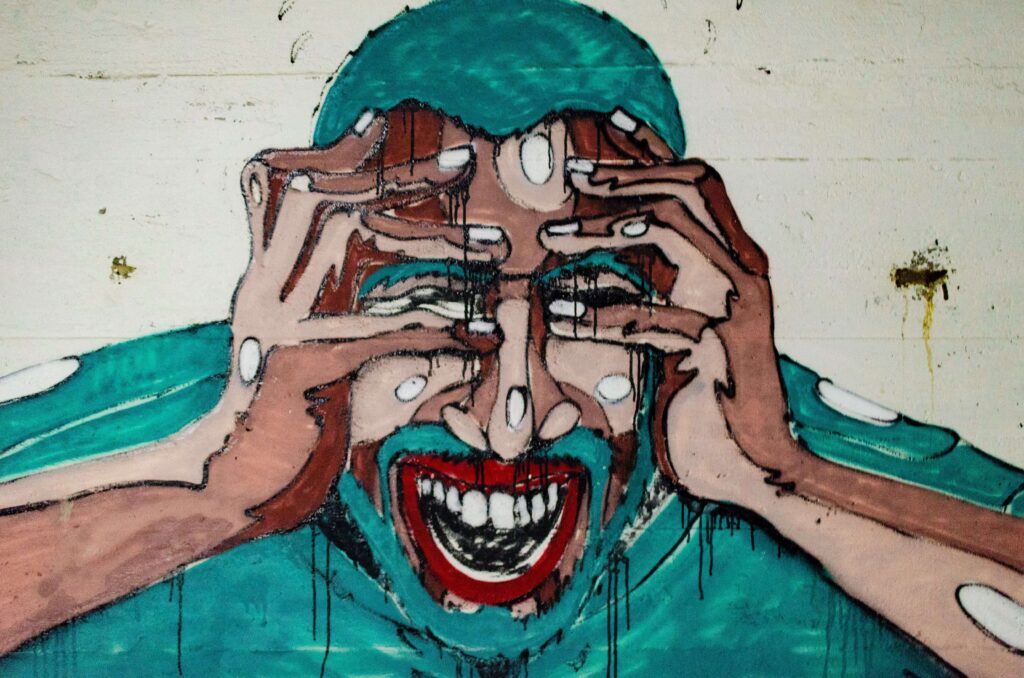

So, we’ve all heard the cliche, “Stress is a killer”, but this seems to be so overused now that people just seem to say it, but don’t really take into consideration the mechanisms behind that statement and how important those mechanisms are in their life.

Evidence from a variety of sources supports the notion that stress and emotional distress relate to dysfunction and hypofunction of the immunologic system.

So, what’s happening under the hood?

You may know by now that when we are stressed, feel fear, anger, resentment, anxiety etc the body sends signals to your brain through transmitting certain neurochemicals such Adrelanine (energy increase hormone – prepares you for fight or flight in a threatening situation) and Cortisol (the stress hormone).

The bodies stress response suppresses non-essential functions (in the moment of threat): Cortisol temporarily suppresses functions like digestion and the immune system to prioritise resources for immediate needs.

This suppression gives us optimum ability to run or fight in moments of immediate threat. This is a mechanism created during evolution to give us the best chance of survival when those sabre tooth tigers came sniffing around!

As with other mammals who share these same mechanisms, the idea is that when the immediate threat is gone, adrenaline and cortisol levels fall and digestion and the immune system come back online. However, in states of persistent stress, fear, anxiety etc, these stress hormones are constantly flooding our bodies, putting our body in constant fight or flight mode, and suppressing functions like digestion and the immune system for much longer periods than evolution prepared us for.

As with other mammals who share these same mechanisms, the idea is that when the immediate threat is gone, adrenaline and cortisol levels fall and digestion and the immune system come back online. However, in states of persistent stress, fear, anxiety etc, these stress hormones are constantly flooding our bodies, putting our body in constant fight or flight mode, and suppressing functions like digestion and the immune system for much longer periods than evolution prepared us for (if you’re stressed all the time, do you have digestion issues or are you ill all the time???).

What is happening to our immune system in chronic stress?

One of the key functions of blood is protection. White blood cells are immune system cells. They are like warriors waiting in your blood stream to attack invaders such as bacteria and viruses. When fighting an infection, your body produces more white blood cells (NHS, no date).

These white blood cells are made up of two types of lymphocyte: T-cells and B-cells. Both types are part of your body’s defense. B-cells make proteins called antibodies to fight pathogens (any organism or agent that can produce disease). T-cells protect you by destroying harmful pathogens and by sending signals that help control your immune system’s response to threats.

T-cells are critical for maintaining immune system function and protecting the body from infections. Chronic stress can have significant impacts T-cells and B-cells.

T-Cell Changes:

- Chronic stress may lead to a decrease in the number and effectiveness of T-cells, particularly cytotoxic T-cells and helper T-cells.

- These changes can compromise the body’s ability to identify and destroy infected or abnormal cells.

B-Cell Changes:

- Chronic stress can suppress the activity of B-cells, which are responsible for producing antibodies to fight off infections.

- Reduction in B-cell function may result in a weakened ability to mount an effective immune response against pathogens.

Shift in Immune Balance:

- Chronic stress may shift the balance between different T-cell subsets, favoring an increase in pro-inflammatory T-cells (highly proinflammatory T cells that induce chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases).

- This imbalance can contribute to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation, which is associated with various health issues.

Impact on Immune Signaling:

- Stress hormones, such as cortisol, can interfere with the signaling pathways involved in immune cell communication.

- Altered signaling may impair the coordination of immune responses, making the body less efficient in recognising and combating threats.

Decreased Immune Surveillance:

- Chronic stress may impair the immune system’s ability to conduct thorough surveillance for abnormal or infected cells.

- This can increase the risk of infections and may contribute to the development or progression of certain diseases.

Dysfunction or imbalance in T-cell responses can contribute to various immune-related disorders, including autoimmune diseases and immunodeficiency conditions.

Autoimmune disorders are conditions where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells and tissues, leading to inflammation and dysfunction – such as:

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA):

- A chronic inflammatory disorder that primarily affects the joints, leading to pain, swelling, and joint damage.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE):

- An autoimmune disease that can affect multiple organs, including the skin, joints, kidneys, heart, lungs, and nervous system.

Type 1 Diabetes:

- The immune system targets and destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, resulting in insulin deficiency and high blood sugar levels.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS):

- An autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system, causing damage to the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibers.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD):

- Includes conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, where the immune system attacks the digestive tract, leading to inflammation and damage.

Psoriasis:

- A chronic skin condition characterized by the rapid buildup of skin cells, resulting in red, scaly patches.

Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis:

- The immune system attacks the thyroid gland, leading to inflammation and an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism).

Graves’ Disease:

- The immune system produces antibodies that stimulate the thyroid gland, causing an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism).

Celiac Disease:

- An autoimmune disorder triggered by the ingestion of gluten, leading to damage in the small intestine.

Vitiligo:

– Causes the immune system to attack and destroy pigment-producing cells in the skin, resulting in patches of depigmentation.

Addison’s Disease:

– The immune system attacks the adrenal glands, leading to insufficient production of hormones, particularly cortisol.

Pernicious Anemia:

– Autoimmune destruction of cells in the stomach lining impairs the absorption of vitamin B12, leading to anemia.

Sjögren’s Syndrome:

– The immune system attacks the glands that produce saliva and tears, causing dry eyes and dry mouth.

Ankylosing Spondylitis:

– An inflammatory arthritis that primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints.

Myasthenia Gravis:

– The immune system targets receptors for acetylcholine, leading to muscle weakness and fatigue.

So, you can see that chronic stress is associated with an increased susceptibility to infections, delayed wound healing, and a higher risk of certain autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. Keeping your body in a constant state of fight and flight can not only affect your digestion but can also affect the functioning of the cells in your blood that act as barriers against disease and infections. It is so crucial that we adopt stress management strategies to help mitigate these negative biological effects on our immune system.

References

Brod, S., Rattazzi, L., Piras, G., D’Acquisto, F. (2014). ‘As above, so below’ examining the interplay between emotion and the immune system. Immunology, 143(3), 311-318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12341.

NHS. (no date) Functions of blood: its role in the immune system. Available at: URL (Accessed: 10 November 2023).

Reis, J., Antoni, M., & Travado, L. (2020). Emotional distress, brain functioning, and biobehavioral processes in cancer patients: A neuroimaging review and future directions. CNS Spectrums, 25(1), 79-100. doi:10.1017/S1092852918001621

Soloman, G, F. (1969) ‘Emotions, stress, the central nervous system, and immunity’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Volume 164 (2), pp. Pages 335-343. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1969.tb14048.x.

Soloman, G, F., Amkraut, A, A., Kasper, P. (1974) ‘Immunity, Emotions and Stress: With Special Reference to the Mechanisms of Stress Effects on the Immune System’, Psychother Psychosom, Volume 23 (1-6), pp. Pages 207-217. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000286644.

Thomas, B, C., Pandey, M., Ramdas, K., Nair, M K. (2002) Psychological distress in cancer patients: hypothesis of a distress model. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 11(2):p 179-185.